And the border guard wept: How we came to film the decisive moments of the fall of the Wall at Bornholmer Straße

I remember the feeling well – a mixture of frustration and disappointment. It was the morning after we’d shot what we thought was going to be some incredibly exciting and spectacular footage of the opening of the Berlin Wall. November 9, 1989, marked the climax and the grand finale of a peaceful German revolution – and it had been a Thursday. But the Spiegel TV news magazine I was working for at the time was only going to broadcast our images three days later, on the following Sunday.

Who would possibly want to see the footage we’d shot that night, three days after the fact, I asked myself. By that time, people all over the world would have already been shown countless images of that historic event over and over again on their television screens.

My trusted colleagues, cameraman Rainer März and his assistant Germar Biester, were both seasoned professionals and had a better sense of things. “What we just experienced,” Rainer insisted, “was something incredibly special.”

It was only in the days thereafter that I began to have hope, especially as I sat in the hotel watching all those special broadcasts and seeing almost identical images of lines of Trabants and jubilant Berliners. Maybe Rainer was right; maybe we truly had gotten lucky that evening.

As it turns out, the images we captured of the opening of the border crossing at Bornholmer Strasse in Berlin are indeed exceptional. UNESCO has even declared them official World Heritage documents, just like Goethe’s oeuvre and Beethoven’s 9th Symphony.

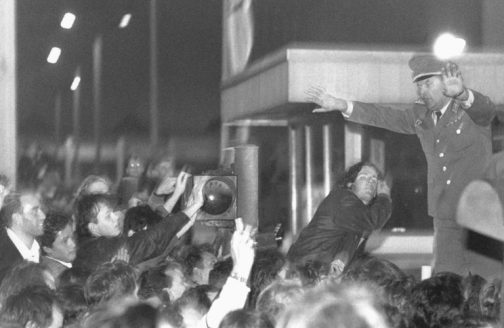

The footage is unique because Bornholmer Strasse was the first border crossing to open on that historic night, and because the images provide proof that the end of the brutal Berlin Wall was not the result of a well-calculated plan devised by the East German Politburo. No, it was something forcibly accomplished by the citizens of the GDR. In fact, the fall of the Wall was the result of citizens pushing aside and storming through an unjust border. To this day, our images show the drama of those hours, the courage of the people gathered there as well as the uncertainty and instability of an oppressive state apparatus teetering on the brink of collapse. Our images document the very moment when fear changed sides – from the people to the state behind the East German dictatorship.

Among the individuals who ventured across the border to West Berlin that night was a young woman who had come directly from a nearby sauna to the checkpoint at Bornholmer Strasse. At the time, she was an unknown physicist. Today, everyone knows her name: Angela Merkel.

If we had stayed sitting in the hotel bar of our East Berlin hotel near the Brandenburg Gate – a hotel designed exclusively for foreign guests – those legendary images would simply not exist. Just a couple of hours prior, Politburo member Gunter Schabowski had held a press conference in which he had uttered the now-famous words that, as far as he knew, the new visa rules for GDR citizens wanting to travel to the West were effective “immediately.”

What exactly did he mean by that statement, and who exactly was allowed to cross the border? Well, these were exactly the questions that I, a freshly arrived newcomer, was debating with my more experienced GDR-correspondent colleagues as we drank our overpriced Radeberger beers on tap in the hotel bar. As far as I can remember, even the most daring and opinionated of my colleagues did not predict that the Berlin Wall would fall and the division of Germany would end that night. As for me, I was just 25 years old and hadn’t a clue about anything.

We sat there, baffled by what was going on and uncertain about what would happen next. That is, until it became clear to us that a hotel bar in Mitte was probably not the best place to carry out our best research. So we packed our things and drove to Prenzlauer Berg, a stronghold of the resistance. Anyone in East Berlin who was dissatisfied with the GDR, and anyone who belonged to the opposition, lived in this area where residential buildings reached right up to the Wall. If anything was going to happen, I thought, it was going to happen here.

It was quiet on the streets, so we ended up at a bar again. There, too, the only topic of discussion was the Schabowski press conference. Nobody knew what it all meant. Soon, however, the first reports started coming in that the Wall was open. It wasn’t actually open yet, of course, but many people in Prenzlauer Berg were curious, impatient and increasingly fearless. So they made their way to Bornholmer Strase. And we went with them.

Thousands of people were already standing at the border crossing. They were restless and jostling to see what was happening at the gate. Eventually they broke into a chorus of chants including “Open the gate, open the gate!” and “We’ll come back, we’ll come back!”

My colleagues and I made our way through the crowd until we found ourselves directly at the boom gate, which was still firmly in place. We immediately got into trouble with the border guards, because to film what was going on, we had stepped over the barrier and were now standing in the transit area. This was an absolute affront to any GDR border guard. One of them demanded to see our passports and threatened to deport us back to the West. I was arguing with him when the bolt on the barrier right next to us suddenly released, the boom gate moved to the side and waves of cheering people made their way to freedom. It was the first hole in the Wall. Only later did the guards at other German-German border crossings start letting people through without any kind of inspection.

And only later did I begin to comprehend what had really happened that night. Together with my team, I conducted interviews with all of those border guards and Stasi officers who had been on duty that night at Bornholmer Strasse. I learned that they’d sent a constant flow of urgent requests to Stasi headquarters for some sort of guidance. They didn’t know what to do; they were scared and alarmed. Nobody had any desire to use force, and everybody in the GDR was already familiar with the meaning of the term “Chinese solution.” The first command that came through from the Stasi leadership was to place the official GDR exit-stamp directly on the passport photo of any person particularly eager to leave; this mark would allow them to identify these individuals at a later date – and provide justification for not letting them back in the country. It was perhaps the last scam visited upon the people by a sinking regime.

I still have contact with some of the officers who were on duty that night, like Lieutenant Colonel Harald Jäger, who ultimately gave the order to push the boom gate aside. This past summer, when Germany’s president invited me to tell the story of that night, Lieutenant Colonel Jäger was in the audience. There have been a number of calls to award him the Bundesverdienstkreuz, Germany’s Federal Cross of Merit. That medal has already been given to the Hungarian Lieutenant Colonel Arpad Bella, who opened the Iron Curtain at the Austrian border in August 1989, thus enabling hundreds of GDR citizens to escape to the West.

Late on the night of November 9, 1989, Lieutenant Colonel Jäger went looking for a quiet place at the Bornholmer Strasse border crossing to have a good cry. He made his way to the processing barracks, only to find a captain already sitting there, head in hands, crying. Jäger is still proud of his decision to open the gate. “Providence brought you there that night,” Jäger’s wife once said to him. “Nope, it was actually the duty roster,” he replied

Georg Mascolo

heads the joint investigative unit of the daily Süddeutsche Zeitung and the public radio and television broadcasters NDR and WDR. He has been based as political correspondent in Washington, D.C.