A war’s end and a fresh start

At 2:41 in the early morning of May 7, 1945, Chief of the German General Staff Alfred Jodl, Commander in Chief of the German Navy Hans-Georg von Friedeburg and Luftwaffe General Wilhelm Oxenius fixed their signatures to the German Instrument of Surrender in a little red school house in Reims, the headquarters of US General Dwight D. Eisenhower. The ceremony was then repeated the next day, with greater fanfare, in the mess hall of a former Wehrmacht pioneer school in Berlin-Karlshorst, the headquarters of Soviet Marshal Georgy Zhukov.

Stalin had insisted on the second event to make it clear to all the world that the German Reich had laid down their weapons on all fronts. This time, it was Chief of the Armed Forces High Command Wilhelm Keitel who signed for the Germans. When he departed, he raised his marshal’s baton, but no one took notice of his farewell. The capitulation took effect at 12:01 a.m. Central European Time on May 9. The war was over.

Adolf Hitler had shot himself in the head ten days earlier in the Führerbunker of the Reich Chancellery in Berlin. For the three weeks following his suicide, the German Reich was presided over by a government in Flensburg under President Karl Dönitz, the Supreme Commander of the Navy. On May 23, all members of the government were arrested by the Western Allies. At the Mürwik naval academy that sunny morning, the Imperial War Flag of Germany was lowered for the last time, never to be raised again. There was no more Third Reich. To put it more bluntly, there was no more German Reich. Supreme authority now lay with the Allied victors.

At that time, no one was capable of imagining that just a few years later, a new German state would appear on the scene in the form of the Federal Republic of Germany; indeed, by accident of fate, it was exactly four years after the capitulation in Flensburg, on May 23, 1949, that West Germany’s Basic Law would come into force.

The German Reich ended in rubble and shame. The shame was manifest – the war of aggression, the cruel reign of the Swastika in occupied lands, the gas chambers of the extermination camps. The Nazi regime had brought the European continent under its yoke, branded as sub-humans the conquered peoples in the east and murdered six million Jews in its death factories.

For the most part, it was Germans, willingly or otherwise, who wreaked the horrors. For almost six years, the Germans had been perpetrators, now they became victims.

By the end of the war, the Germans started suffering to no end – flight and expulsion, the bombing war by the Royal Air Force and its US comrades, the mass raping of civilians committed not only by the Red Army, prisoner-of-war and detention camps, humiliation and deprivation, hunger and exposure was our lot. But there is no question about it: German suffering was born directly from our own atrocities.

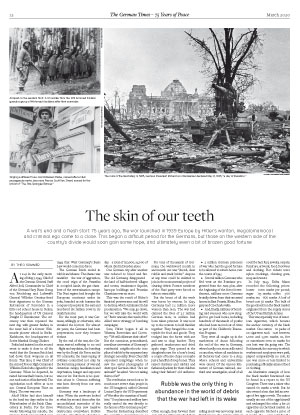

Germany was a landscape of ruins. When the survivors looked at what lay around them after the unconditional surrender of the Wehrmacht, they saw massive destruction everywhere. Rubble was the only thing in abundance in the world of debris that the war had left in its wake: around 400,000,000 cubic meters of it.

From the beginning of January until the end of April, 1945, British Bomber Command alone conducted 79,000 sorties. In the last four months of the war, Bomber Command and the US Air Force together dropped 370,000 tons of high-explosive and incendiary bombs over the Reich, which amounted to one-quarter of the total dropped on Germany during the entire war. This final four-month phase of the war accounted for one-quarter of the half-million people who were killed by Allied air attacks on German cities over the course of the war. During this period, the bombing war claimed and average of 1,000 casualties a day – a total of 130,000, 25,000 of whom died in Dresden alone.

One German city after another was reduced to blood and fire. The old Germany disappeared – the land of half-timbered villages and towns, renaissance façades, baroque buildings and Prussian Classicism was no more.

This was the result of Hitler’s fanatical perseverance and his will to destroy, which culminated in his proclamation: “We may go down, but we will take the world with us.” But it was also the result of the Allied terror strategy of bombing campaigns.

Sure, Hitler began it all in Warsaw, Rotterdam and Coventry: “We will obliterate their cities!” But the conscious, premeditated, merciless conversion of Germany’s residential neighborhoods into piles of rubble by far surpassed any strategic necessity. Even Churchill expressed misgivings when he saw the aerial photographs of destroyed German cities. “Are we animals?” he asked. “Are we taking this too far?”

The retribution turned out to be much more severe than people in the US imagined, cabled General Lucius Clay to the US Department of War after the cessation of hostilities. “Our planes and artillery have really carried the war directly to the homes of the German people.”

Theodor Eschenburg described the resulting circumstances as follows: “The number of homeless people was in the millions. In many cases, entire families lived in a single room. Cellars and attics, barracks and Quonset huts, ruins and warehouses – anything was used as a shelter,” wrote the political scientist from Tübingen. “In the inner cities where narrow streets and alleyways had been the norm, new paths formed over the mountains of rubble. Forsythias, lilacs and jasmine grew freely and furiously in the gardens of houses that no longer stood.”

According to official statistics, the British occupation zone had an average of 6.2 square meters of living space per person. Living quarters in the American, Russian and French zones were only insignificantly more spacious.

For tens of thousands of Germans, the watchword month in and month out was “shovel, clear rubble and stack bricks.” Anyone at any time could be enlisted to join in the monumental project of clearing debris. Former members of the Nazi party were forced to take on extra shifts.

But the brunt of all the work was borne by women. In 1945, Germany had 7.5 million more women than men. The war had claimed the lives of 3.7 million German men; 12 million had been taken prisoner. It was now up to the women to hold families together. They foraged the countryside for food and goods. They trudged into the forest with axe and saw to chop lumber. They gathered mushrooms and dried apple rings. They queued at the slaughterhouse for a boar’s head, a couple of horse chops or maybe just a handful of soup bones. They raised chickens and rabbits and fashioned jackets for their children using their fathers’ old uniforms. Often enough, they forwent their own rations of bread to feed their children. And these Trümmerfrauen, the rubble ladies as it were, have become legendary. They cleared the lots and streets in every city and town across Germany.

Moreover, conditions in defeated and occupied Germany were pure chaos. Millions of people were on the move as part of the most comprehensive mass migration of modern times:

- 300,000 survivors of the concentration camps

- 8.5 million forced laborers, the former work slaves of the Third Reich, who were now displaced persons awaiting return to their home countries, were left to provide for themselves any way they could, which often meant plundering the surrounding region and raiding local farms

- 5 million German prisoners of war who had the good fortune to be allowed to return home over the course of 1945

- Several million Germans who fled west as the Russians progressed from the east, plus, after the beginning of the forced resettlement, millions more Germans brutally driven from their ancestral homes in East Prussia, Silesia, Hungary and Czechoslovakia

- And, finally, millions of bombing raid evacuees who now struggled to get back home, including hundreds of thousands of youths who had been moved out of cities as part of the Children’s Evacuation Program.

They were all caught up in the maelstrom of chaos following the end of the war in Germany, where hardly one stone still rested on another, where all machines in all factories had come to a stop, where schools and universities were closed. Of the 60,000 kilometers of German railroad, one-third was unnavigable; a half of all rolling stock was now scrap metal. Furthermore, the system of food provisioning had more-or-less completely broken down.

The only option left was to “organize” things. Countless army supply depots and food storage facilities were plundered in the bedlam immediately following the war. After that, people just made do as best they could. Parks were transformed into vegetable gardens; a bartering economy took hold; people begged at farms; others resorted to “Fringsen” – stealing in small quantities but with the blessing of Cologne’s Cardinal Josef Frings, who, in his New Year’s sermon, granted his flock prophylactic absolution for taking what they need in order to live, particularly coal in times of emergency.

Bartering was a slippery slope to the black market, where anything could be had: furs, jewelry, carpets, furniture, artwork, food, footwear and clothing. Hot tickets were nylon stockings, chewing gum, soap and sweets.

In July 1945, Erika Mann recorded the following prices: butter – 1000 marks per pound; sugar – 175 marks; coffee – 500 marks; tea – 600 marks. A loaf of bread cost 30 marks. The bulk of the goods sold on the black market originated from the supply stores of the US and British Armies.

This was especially true of American cigarettes, which became the anchor currency of the black market. One carton – 10 packs of 20 cigarettes each – cost between 1,000 and 1,500 marks; so, five or sometimes even 10 marks for one butt was the going rate. The Reichsmark, the currency in which workers and employees were paid, played comparatively no role; its use was more-or-less limited to purchasing officially rationed food or clothing.

An illustrative example of how the black market functioned can be found in a report to the US Congress. There was a miner who earned 60 marks a week. But he also owned a hen that laid an average of five eggs a week. The miner usually ate one of the eggs himself and exchanged the other 4 for 20 cigarettes on the black market. As each cigarette fetched a price of 8 marks, the 4 eggs sold for the equivalent of 160 marks. Thus, on a weekly basis, the hen earned almost 3 times more than her owner.

According to estimates at the time, a half of Germany’s commercial revenue derived from bartering and the black market, and was thus beyond the reaches of state regulation. It goes without saying that the black market was fertile ground for organized crime. For many normally law-abiding citizens, however, the black market was a savior, as it allowed people to meet needs that they could not otherwise fulfill.

Decades after the end of the war, Germans were at odds about how to classify what had happened in 1945: Was it a collapse or liberation? To be sure, this question was seldom asked during that fateful spring. But the answer is: both. It was a collapse as well as a liberation.

The collapse was patently obvious. Many had survived by the skin of their teeth. Countless Germans had lost their homes, others their homeland. The cities lay in rubble. Industry, commerce and manufacturing all but ceased to exist. Government stopped functioning; schools and universities remained closed for an extended period of time.

To most Germans, occupation by the Allied victors at first felt more like oppression than liberation. Sure, people were liberated from the fear of getting killed in the next night of bombing; from the fear of losing a husband or a son on the front; from the fear that the war could go on forever. But these were then replaced by new fears: How do I survive until tomorrow? What will become of me – and of Germany? How complicit was I in all that happened under Hitler? Am I guilty for things that I did, or thought, or tolerated? Am I guilty for not having protested all the injustice?

Those who truly felt liberated after the war were the political opponents of the Nazi regime, those who were active in the resistance, the Jews, the Sinti and Roma and the homosexuals who were persecuted. They all breathed a sigh of relief in May 1945.

However, all those whose naïveté and idealism had led them to believe in Hitler experienced the end of the Third Reich as an utter collapse. They became embittered by the miscarriage of their illusions, by the futility of their devotion and the hollowness of their suffering – and then fully so when they toured the liberated concentration camps, as decreed by the occupying powers, and saw the mountains of corpses; once and for all they had to relinquish the cold comfort that the documentary films and photographs displayed everywhere after the war were mere phonies produced as Allied propaganda.

Theodor Heuß, who in 1949 became the first president of West Germany, once described the end of the war as follows: “In essence, this eighth of May remains the most tragic and questionable paradox of history for all of us. But why? Because we were at once redeemed and destroyed.”

Redeemed and destroyed: With most Germans, the feeling of having been destroyed outweighed the relief of redemption. In 1985, only after 40 years had passed could another president of the Federal Republic, Richard von Weizsäcker, count on widespread understanding when he said:

May 8 was a day of liberation. It liberated all of us from the inhumanity and tyranny of the National Socialist regime. Nobody will, because of that liberation, forget the grave suffering that only started for many people on May 8. But we must not regard the end of the war as the cause of flight, expulsion and deprivation of freedom. The cause goes back to the start of the tyranny that brought about the war. We must not separate May 8, 1945, from Jan. 30, 1933.

Immediately after the war, few Germans were in a state of mind to entertain such weighty thoughts. Coping with everyday life exhausted all of their strength; coping with the past was a “luxury” that would only come much later. And those who brought feelings of guilt upon themselves felt an extra weight of oppression.

In an initial wave of denazification, all office holders in West Germany were stripped of their jobs: 150,000 working in public service and 73,000 employed in trade and industry. They received neither a salary nor a pension; they were now permitted only to do “ordinary work.” Around 180,000 were detained, sometimes for years.

In the second wave, denazification procedures resembled a bureaucratic inquisition, culminating in the questionnaire campaign by which the Western Allies sought to vet the Germans by tooth and nail. The questionnaire comprised 131 questions. It became both feared and ridiculed – ridiculed for its many pointless individual questions and feared because the future of many Germans hinged on the questionnaire’s findings.

By March 1946, 1.4 million questionnaires had been submitted in the American zone, 742,000 of which had been processed. The results were that 19 percent would be fired; 7 percent were recommended to be fired; 25 percent would be fired at the sole discretion of their employer; and in 49 percent of cases, there was no evidence of any National Socialist activity. One-half of one percent of those examined were found to have verifiably aided the resistance.

The flaws of this process, the harassment it unleashed and, ultimately, the solidarity it engendered induced the US military government to soften its approach as early as in January 1946. The Law for Liberation from National Socialism and Militarism established 545 German Spruchkammer – or civilian tribunals – employing 22,000 staff that would now deliver verdicts on the basis of the 13 million submitted questionnaires. This process concluded with 3.5 million accusations and 950,000 trials. In the three-and-a-half years of denazification ending in 1948, 1,549 Germans were found to be “major offenders,” 21,600 “offenders,” 104,000 “lesser offenders” and 475,000 “followers.” The tribunals issued 9,000 prison sentences, more than 500,000 fines and 25,000 seizures of assets. The Soviet occupation zone saw 30,000 war-criminal trials, 200,000 Nazis banned from public service and industry, 20,000 – of 40,000 – teachers fired and the delivery of 500 death sentences.

The denazification trials were accompanied by the process of dismantling German industry and the exaction of reparations by the victorious powers. Germany was to make amends for the destruction it had wreaked from the Atlantic to the Volga. The Potsdam Agreement stipulated that German production would be reduced to between 50 and 55 percent of its capacity in 1938, which corresponded to totals reached in the bleak crisis year of 1932. Germany’s primary production was to be set at 40 percent of the 1936 levels, which would deplete the pharmaceutical industry by 80 percent. The production of gasoline, ball bearings, synthetic rubber and radioactive material was forbidden altogether, along with commercial shipping and aviation.

When the beaten Germans looked back six months after capitulation, they saw nothing but gloom and doom. Add to this mix the beginnings of the division of Germany into East and West. While the East was not yet barricaded with barbed wire and walls, officially permitted border crossings were few and far between.

Those wanting to get from East to West or West to East had to hoof it across the “green border” through forests and fields avoiding Soviet control points and patrols. Many were apprehended and detained while attempting to cross. One woman from Thuringia – in the Soviet zone – who wanted to visit the Schwabenland – in the West – was intercepted between the towns of Probstzella and Hof and forced to spend several days in a prison cell. While detained, she noticed that a former inhabitant of the cell had carved these words into the limestone wall: “Here I sit, a German imprisoned in Germany / Because I went from Germany to Germany.” The land reform that took effect in the Soviet zone in the fall of 1945 marked the beginning of the expropriation of the middle class and the oppression of all “bourgeois elements,” which spurred the eventual division of Germany.

But there were also rays of hope, which grew brighter and ever more frequent. Life amid the ruins gradually began to normalize. People settled in to their world of rubble, became accustomed to the black market and its cigarette currency, resigned themselves to the occupation and established new political organizations and new administrative bodies. They rolled up their sleeves, spat into their palms and went to work. Under the most adverse conditions they learned to develop initiatives, to improvise and to make ends meet, while embracing humility and accepting that life may be a long hard slog.

Already in the first fall after the war, news bulletins published by the military government became more and more frequently supplanted by German newspapers. The schools and universities opened the gates anew. And, most astonishing of all, culture began to flourish again. Theaters that Goebbels had closed in September 1944 raised their curtains and found audiences eager for artistic and cultural experiences. Gotthold Lessing’s Nathan the Wise was the favorite. At long last, concert halls and churches performed works by those composers who had been outlawed by the Nazis, including Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy, Paul Hindemith, Arnold Schönberg and Igor Stravinsky. And museums exhibited “liberated art” that for 12 years had been banned as “degenerate.”

In June 1945, author and satirist Erich Kästner managed to capture the spirit of optimism: “If you try to describe what you’re experiencing all around you, only antiquated terms come to mind, like ‘gleams of hope,’ ‘aurora,’ ‘creative joy,’ ‘rush of exhilaration’ and ‘vital courage.’ The stomach churns but the eyes sparkle.”

The title of Thornton Wilder’s play, The Skin of Our Teeth, captured the sentiments of most Germans at the time. From today’s vantage point, even we Germans can say that we got away lightly, that is, by the skin of our teeth.

First, Germany was spared from being as fragmented as the Allies had originally contemplated. While Roosevelt had imagined splitting the country into five or seven states, Churchill envisioned one state in the west, one in the north and one in the south. The eventual division of Germany into east and west, a burden born by the Germans for 40 years, was not ultimately an element of the punitive peace, but rather the result of the Cold War, which began in earnest in 1945. When the East-West conflict subsided, the Germans could finally redress the division.

Second, this Cold War, as paradoxical as it may sound, had its upsides. As opposed to being further ostracized and minimized, both Germanys, ours and theirs, rose in rank rather quickly to become something akin to guest-victors. Almost immediately, they took on crucial roles within the opposing state systems. Pariahs became partners.

Third, we had tremendous luck with respect to our economy. Instead of the planned $80 billion in reparations, the Allies ultimately exacted only $12 billion. But to the extent that they succeeded in their process of de-industrialization, by means of their dismantling of German factories right up to 1950, in many cases this proved to be a blessing in disguise. The outdated facilities went to the victors, but the Germans, after the currency reform, were able to succeed in modernizing their industrial sector to state-of-art standards. Germany’s “economic miracle” of the 1950s relied heavily on this fortuitous upgrade.

And there is still a fourth dimension to the luck Germans experienced in the immediate postwar period: the fact that America’s first successful test of an atomic bomb was on July 16, 1945, and not six months earlier. Had “Little Boy” and “Fat Man” already been available, the first two targets of America’s nuclear arsenal would likely have been German cities. Hiroshima and Nagasaki would not have been incinerated and contaminated; it would have been Berlin, perhaps Munich, Cologne, Bremen – or Dresden.

In 1945, the Germans oscillated between hope and fear, the hope sprouting only with hesitation. A flyer published by the resistance movement known as the White Rose had once augured that “we will forever be the people that are hated and outcast by all of the world.” The fact that this prophecy proved wrong will forever be a credit to those men and women who, 75 years ago, set out to craft a better future for our people on the rubble and wreckage of a loathsome war. Without them, we would not be what we are today: not hated and outcast, but accepted and respected – esteemed not spurned.

Theo Sommer

is Executive Editor of The German Times.