Alba’s basketballers are taking the game to the classroom

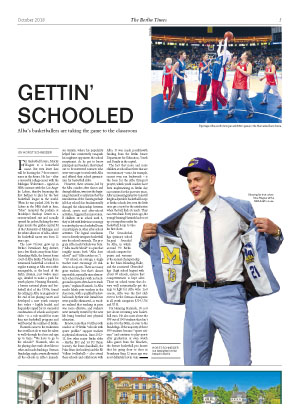

For Basketball lovers, Moritz Wagner is a household name. But even lesser fans will be hearing the 7-foot center’s name in the future. He has – after a successful college career with the Michigan Wolverines – signed an NBA contract with the Los Angeles Lakers, thereby becoming the first Berliner to play for the best basketball league in the world. When he was picked 25th by the Lakers in the NBA draft in June, “Moe” mounted the podium at Brooklyn’s Barclays Center in a custom-tailored suit and casually opened his jacket, flashing the two logos inside: the golden capital M of the University of Michigan and the white albatross of Alba, where his basketball career was born 12 years ago.

The now 7-footer grew up in Berlin’s Prenzlauer Berg district, just a few blocks away from Max-Schmeling-Halle, the former home court of Alba Berlin. The leap from intramural basketball at school to regular training at Alba was rather manageable, as the head of the Berlin division, just twelve years ago, decided to make a push for youth players. Henning Harnisch, a former national player and basketball idol of the 1990s, found his calling in Alba management at the end of his playing career and developed a new youth concept that today – highly lauded and frequently copied for its successful combination of schools and sports clubs – is a role model for more than just basketball programs and well beyond the confines of Berlin.

Harnisch came to the realization that it will not do to wait for talent to walk through the door and sign up to train: “We have to go to the schools!” Harnisch, who in his playing days sunk shots like no other and made dunking a German Bundesliga staple, eventually visited all the schools in Alba’s immediate vicinity, where his popularity helped him consistently vanquish his mightiest opponent: the school receptionist. As he got to know principals and teachers, they turned out to be interested contacts who were very eager to work with Alba and offered their school gymnasiums for basketball clubs.

However, these sessions, led by the Alba coaches after classes and during holidays, were just the beginning. Harnisch’s realization that the introduction of the Ganztagsschule (all-day school) has fundamentally changed the relationship between school, sports and after-school activities, triggered his innovation. If children sit in school until 4, they’re left with little time or energy to actively play on a basketball team or participate in other after-school activities. The logical conclusion was to directly integrate basketball into the school curricula. The program Alba macht Schule was born. (“Alba macht Schule” is a pun that roughly means both “Alba does school” and “Alba catches on.”)

“At school, on average, a single teacher must encourage 28 children to do sports. There are many great teachers, but that’s almost impossible, especially since elementary school teachers with no background in sports often have to teach sports,” explains Harnisch. So Alba macht Schule puts teachers in the classroom, with a qualified basketball coach by their side. Initial fears were quickly eliminated, as teachers realized that teaching in pairs was more effective, and students were instantly excited by the new life being breathed into physical education.

By now, more than 50 Alba youth coaches at 19 Berlin “schools with sports profiles” support teachers in physical education. Since 2012–13, five other major Berlin clubs – Hertha BSC and 1st FC Union (soccer), the Foxes (handball), the Polar Bears (ice hockey) and the BR Volleys (volleyball) – also attend these schools and collaborate with Alba. It was made possiblewith funding from the Berlin Senate Department for Education, Youth and Family in the capital.

The fact that more and more children at school have lives that are too stationary – some, for example, cannot even run backwards – is the basis for the Alba Kitasport project, which youth coaches have been implementing in Berlin day care centers for the past two years. Alba’s pioneering initiative to install height-adjustable basketball hoops at Berlin schools lets even the little ones get a taste for the satisfaction when the ball finds its mark. They can even dunk. Forty years ago, the young Henning Harnisch had to set up a trampoline under his basketball hoop to take his first shots.

The Grundschulliga (primary school league) founded by Alba, in which around 90 Berlin schools compete for points and victories at the annual championship in the Max-Schmeling-Halle, and the associated Oberschulliga (high school league) with about 80 schools, ensures that competitiveness is kept alive. Those on school teams that do very well automatically get the urge to fight for Alba wins. Last season, Alba was the first club ever to be the German champions in all youth categories (U14, U16 and U19).

For Henning Harnisch, it’s not just about recruiting new basketball stars. He also cares about the 999 out of 1000 students that don’t make it to the NBA, or even to the Bundesliga. If the majority of these 999 students become “sports citizens” and continue to play sports after graduation or even watch Alba games from the bleachers, the former basketball pro knows that his going door to door in Prenzlauer Berg 12 years ago was most definitely not in vain.

Published in “The Berlin Times – A special edition of The German Times marking October 3rd, the Day of German Unity.”

Horst Schneider

is a basketball writer based in Berlin.