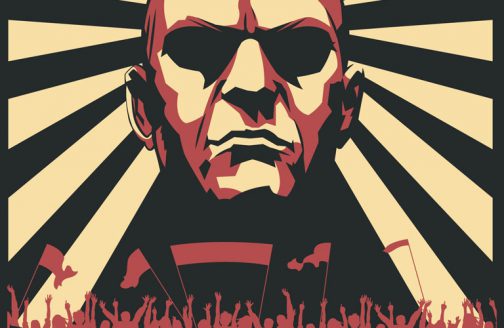

Authoritarian advantage: The struggle for a liberal world order is occuring not just outside the West but also within it

A character in the Hemingway novel The Sun Also Rises, asked how he went bankrupt, responds, “gradually and then suddenly.” That is a fair description of how the world order collapsed before the two world wars. Unfortunately, Americans and Europeans have since forgotten how quickly it can happen, how quickly graver threats than we anticipate can emerge to catch us physically and psychologically unprepared. One would think it hard to embrace a 1930s mentality with the benefit of the knowledge of what happened in the 1940s, but we continually comfort ourselves that the horrors of 75 years ago cannot be repeated. We see no Hitlers or Stalins on the horizon, no Nazi Germany, no Imperial Japan, no Soviet Union. We believe that the leaders of today’s potential adversaries, the Vladimir Putins and Xi Jinpings, are just run-of-the-mill authoritarians who just want a little respect and their own share of the international pie. We forget, of course, that people in the 1930s felt the same way about Hitler’s Germany and Imperial Japan – the two self-proclaimed “have-not” nations in the international system.

There are always dangerous people out there, with resentments both legitimate and illegitimate, lacking only the power and the opportunity to achieve their destiny. They are constrained by the powers and forces around them – the “order,” whatever it may be; so they never have a chance to reveal their true selves, even to themselves. The circumstances in which Hitler, Stalin and Mussolini rose to power – a world in which no nation was willing or able to sustain any kind of international order – gave them ample opportunity to show what they were capable of. Had there been an order in place to blunt those ambitions, we might never have come to know them as tyrants, aggressors and mass killers.

Today, we know a Putin with grand ambitions but not yet the capacity to realize them. He reveres Stalin but he is not Stalin. But what would a less-constrained Putin be like? What would a Russia that had restored its Soviet and imperial borders be like? Today, a more powerful China is abandoning the cautious foreign policies of Deng’s weaker China. What will an even more powerful and less constrained China be like? Who can say whether either of these powers might in time become a threat on a par with those we faced in the past if they are allowed to expand their regional and global influence by military means?

We have taken too much solace from the fact that our opponents are not communists, but merely authoritarians. During the Cold War, people like Jeane Kirkpatrick argued that Americans had nothing to fear from authoritarianism. It was the communist governments that threatened democracy. Authoritarian governments would eventually evolve into democracies if given enough time and security against armed radicals, but “totalitarian” communism was forever. Of course, this turned out to be anything but the truth. Communist governments in the Soviet Union and Eastern and Central Europe did fall. In the Soviet Union and elsewhere, governments attempted to carry out peaceful reforms and to open the system, which ultimately led to the establishment of democracies, briefly in Russia and longer-lasting in Eastern and Central Europe. Authoritarianism has proved more durable, less susceptible to internal pressures for reform and so far more capable of withstanding the liberal pressures from beyond their borders.

One reason may be that communism sprang from the same Enlightenment roots as liberalism. In many ways it competed on the same plane, and proved unable to compete. Because communism proposed such an extreme version of the Enlightenment, it conflicted even more with human nature than liberalism did, and so, on the one hand, had to impose its system with greater brutality, and, on the other hand, was even more likely to fall short of its own promises. It offered so much that was appealing to the human soul – the promise of justice and true equality, an end to materialism and greed – but it also demanded more than humans could give and ensured a far greater gap between dream and reality. When it failed to deliver, it suffered a crisis of confidence. When it was also then deprived of geopolitical successes and fell behind in the Cold War competition for power and influence, even Soviet leaders had a hard time reconciling the promise of the ideology, in which they placed so much faith, and the reality of its failure, just as George F. Kennan had predicted.

Authoritarians do not have the same vulnerability. The case for authoritarianism during the Cold War was that it was traditional, organic and natural, yet it is perhaps the very naturalness of authoritarianism that makes it a bigger threat. It appeals to many of those elements of human nature that liberalism does not satisfy – the desire for order, for strong leadership and, perhaps above all, the yearning for the security of family, tribe and nation. If the liberal world order stands for individual rights, freedom, universality and equality regardless of race or national origin, for cosmopolitanism and for tolerance, the authoritarian regimes of today stand for the opposite, and in a very traditional and time-honored way. A Counter-Enlightenment sprang up in the late 18th and early 19th centuries in response to the French Revolution, but also in response to some of the basic tenets of Enlightenment liberalism. Counter-Enlightenment thinkers like Johann Gottfried Herder and Joseph de Maistre condemned the celebration of reason, which they insisted could not capture the ineffable human relationships “that make a family, a tribe, a nation, a movement, any association of human beings held together by something more than a quest for mutual advantage,” as Isaiah Berlin wrote in his essay “Counter-Enlightenment.” Cosmopolitanism, in this view, was “the shedding of all that makes one most human.” Humans were “not made for freedom”; they could find happiness only under “wisely authoritarian governments.”

Such anti-liberal views informed the German struggle on behalf of Kultur and the primacy of the state over the individual in World War I; they informed the fascist movements in the interwar years; in Asia, they inspired a defense of what used to be called “Asian values,” which emphasize community over the individual, harmony over freedom. Today they inspire Viktor Orbán’s celebration of “illiberalism.” The present Chinese government’s critique of liberalism is not so much a communist critique as it is a conservative critique. Just as German authoritarians did in the Weimar years, the Chinese criticize the “endless political backbiting, bickering and policy reversals” that “retarded economic and social progress,” as a Reuters report put it in 2017. Putin and his political counselors have made much the same argument. Radical Islam is nothing if not a rejection of Enlightenment thinking in favor of spirituality and rigid adherence to religious tradition. The Counter-Enlightenment critique of liberalism will always appeal to those who fear that their traditions and beliefs are undermined by the cold materialism of the modern liberal world. It was not globalization that caused the backlash among such peoples; it was the globalization of liberalism.

While we were grateful when communism collapsed, the fact remains that the liberal world order flourished with communism as the enemy. It is doing less well against a Counter-Enlightenment that plays more effectively on liberalism’s failings and insecurities. Mikhail Gorbachev had more in common with liberals in the West than he did with many of his own people. Putin, with his rebukes of gay rights and feminism, his condemnation of the “genderless andinfertile” morality of the liberal West, his support for the Russian Orthodox Church and for conservative traditions in general, may well speak for the majority of Russians in a way that Gorbachev did not.

And Putin’s message resonates in a Western Europe where disenchantment with liberalism, and the immigration it permits, is rising. It even resonates in the United States. Patrick Buchanan called Putin the voice of “conservatives, traditionalists and nationalists of all continents and countries” who were standing up against “the cultural and ideological imperialism of a decadent West.” These days, if the polls are to be believed, favorable views of Russia’s “strong leader” have grown, at least among Donald Trump’s supporters. Putin has positioned himself as the leader of the world’s “socially and culturally conservative” common folk against “international liberal democracy,” as M. Steven Fish wrote recently in the Journal of Democracy, and there are probably more of those common folk around the world, including in the West, than there ever were committed communists. That is why Russian penetration into the political systems of the United States and Europe has been so effective. It has exploited the truly dangerous fissures in Western society, which are not based on class, as the Marxists wanted to believe, but on tribe and culture.

If so, the challenge to democracy today is greater than it was during the Cold War, when, after all, democracy spread across the globe. We must abandon the post-Cold War myth that liberalism is the natural end point of human evolution, just because it triumphed over communism. Five thousand years of recorded history suggest that it is not. Our belief that peoples at all times share a desire for freedom, and that this universal desire supersedes all others, is an incomplete description of the human experience. In troubled times – yet not only in troubled times – people seek outlets for anger and resentment, for fear and hatred of the “others” in their midst. Those who have suffered defeat and humiliation, such as Germans after World War I or Russians after the Cold War, often find that democracy offers insufficient solace and insufficient promise of revenge and justice, so they look to a strong leader to provide those things. They tire of the incessant arguing over national budgets and other trifles while the larger needs of the nation, including spiritual and emotional needs, go unaddressed. We would like to believe that, at the end of the day, the desire for freedom trumps these other human impulses. But there is no end of the day. Human existence is a constant battle among competing impulses – between self-love and the love of others, between the noble and the base – and because those struggles never end, the fate of liberalism and democracy in the world is never settled.

That struggle is not just occurring outside the West, but also within it. When Americans on both the left and right scorn “democracy promotion,” they’re usually thinking of Iraq and Afghanistan, or Egypt and Libya. They’re not thinking of Poland or Hungary or Italy. American conservatives like to argue that democracy is a product of Western civilization and of Judeo-Christian culture and values, with the implication that it is only in these societies that we should support democracy – not in, say, Muslim societies where these traditions are presumably lacking. But setting aside whether democracy is possible in Muslim countries – it is and has been – what makes us so confident that democracy is guaranteed in the West? It was in the Christian West that fascism first arose and in which the ideas of communism were invented. It was in the Christian West that democracy collapsed after World War I. And it is in the Christian West, as much as anywhere, that democracy is at risk today.

Robert Kagan

is a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and a member of the Council on Foreign Relations. A co-founder of the Project for the New American Century, he is also a contributing columnist for The Washington Post and a contributing editor at The New Republic