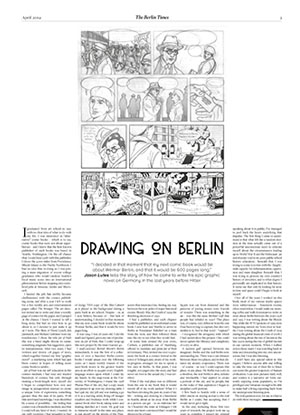

Berlin: An epic graphic novel

I graduated from art school in 1991 with no clear idea of what to do with my life. I was interested in “alternative” comic books – which is to say, comic books that were not about superheroes – and I knew that the best-known publisher of such books was based in Seattle, Washington. On the off chance that I could land a job with this publisher, I drove the 3,000 miles from Providence, Rhode Island, to the Pacific Northwest. I had no idea that, in doing so, I was joining a mass migration of recent college graduates who would catalyze Seattle’s local music scene into an international phenomenon before stepping into entry-level jobs at Amazon, Adobe and Microsoft.

I landed the job, but swiftly became disillusioned with the comics publishing scene, and after a year I left to work for a free weekly arts and entertainment paper called The Stranger. The art director invited me to write and draw a weekly page of comics for the paper, and I jumped at the chance. I knew I wanted to tell a long story, but had no idea how to go about it, so I decided to just make it up as I went. The films of David Lynch, Jim Jarmusch, and Richard Linklater were my touchstones. I chose the title Jar of Fools the way a band might choose its name: something enigmatic but suggestive, open to interpretation. After two years, I had written and drawn 128 pages of story, which together formed my first “graphic novel” (a marketing term which had just been coined in hopes of selling more comic books to adults).

Jar of Fools was my self-education in the comics medium. I had read and studied hundreds of comics, but only through making a book-length story myself did I begin to comprehend how text and image in juxtaposition interact to create a unique form of expression, something greater than the sum of its parts. With this newfound knowledge, I was electrified by a sense of possibility – the feeling that comics was a boundless medium, and that I could tell any kind of story I wanted. In my early twenties, I had struggled to find something to say, but now I wanted to say everything. What subject could possibly grant me that possibility?

It was in this state of mind that I was flipping through a magazine and happened across a half-page advertisement for a book of photographs called Bertolt Brecht’s Berlin: A Scrapbook of the Twenties. I foggily recall one line of evocative ad copy: “And the jazz bands played on as the world spun out of control.” I knew next to nothing about Berlin in the 1920s, beyond having heard my parents’ 1958 double LP of Die Dreigroschenoper (The Threepenny Opera) once or twice as a child, and fragments of dodgy VHS copy of the film Cabaret as it played in the background during a party back in art school. Despite – or, as I now believe, because of – this lack of understanding, I decided in that moment that my next comic book would be about Weimar Berlin, and that it would be 600 pages long.

It was 1994. I was 26 years old. I did the math and figured, given my rate of production on Jar of Fools, that I could wrap up this new project by the time I turned 40.

I mail-ordered Bertolt Brecht’s Berlin immediately. It was the first of a collection of over a hundred Berlin-centric books I would amass over the following years, as I made weekly rounds of the used-book stores in the greater Seattle area in an effort to acquire every English-language source upon which I could lay my hands. In the map room at the University of Washington, I found the 1928 Pharus Plan of the city, had a copy made and pinned it up over my drawing table. I had quit my day job and was making a go of it as a starving artist, living off meager royalties and freelance work while I consumed book after book, taking notes and making sketches as I went. My goal was to immerse myself in the time and place, to put myself on the streets of the Prussian capital and imagine what it was like to be at ground level while momentous events unfolded in real time. After two years of research, having never set foot in the actual city of Berlin, I felt I was ready to start.

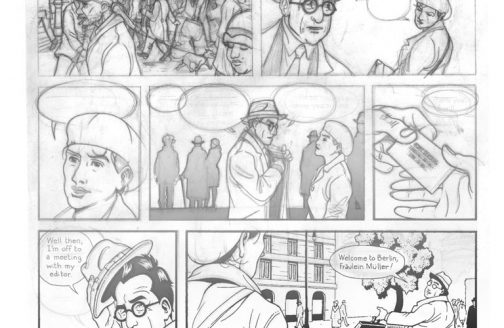

I had come up with two main characters: Kurt Severing, a jaded Berliner and journalist writing for Die Weltbühne; and Marthe Müller, an ingenuous young woman from Cologne who has come to study art in the big city. My strategy was to follow these two into the metropolis, improvising the story one scene at a time, peeling off to pursue any secondary characters that interested me, finding my way between the tent-poles of major historical events: Bloody May, the Crash of 1929, the Reichstag elections of 1930.

I had a publisher, and each chapter would be published as an individual comic book. I sent Kurt and Marthe to arrive in Berlin at Potsdamer Bahnhof on a train from the west, and then followed them into the city to see what they would find.

At some time around the year 2000, Carlsen, a publisher out of Hamburg, offered to translate and print Jar of Fools in Germany. They invited me over to promote the book at a comics festival in the town of Erlangen and, aware of my workin-progress, arranged for me to spend a few days in Berlin. At that point, I was roughly 200 pages into the story, and had never set foot in the actual city. I was terrified.

What if the real place was so different from the one in my book that it would render all of my work useless? What if I had been devoting the past six years of my life – writing and drawing in a basement in Seattle, about as far away from Berlin as a person can get – to an elaborate lie? As I boarded the train at Erlangen I felt more and more convinced that I would be shown to be a fraud.

I remember when the first buildings on the outskirts started to drift past by the window. The sun was setting; abandoned industrial buildings were dappled in golden light. Absurdly, I was not prepared for the fact that everything would be in full color (my comic is drawn in black-and-white), and in particular how green it was. Springtime in Berlin, to someone who has only known the city through old photographs, is astonishing.

I got off the train (as Kurt and Marthe had done in the first chapter of my book) and wandered aimlessly. I was in a heightened state of awareness, where every facade was cut from diamond and the patterns of paving stones were fractals of wonder. There was something in the air – was this the same Berliner Luft that people had inhaled in 1930? This place was, of course, very different from the one I had been trying to capture, but also very similar to it. And in that word – “capture” – I recognized the arrogance with which I had undertaken this project. One could never capture the vibrancy and complexity of a city so alive.

A sudden gulf opened between my imaginary Berlin and the real Berlin now surrounding me. There was a vast distance between these two places, and in that distance my anxiety evaporated. There was – of course – no way I could capture this place, or any place. My Berlin was a city in a shoebox; the real Berlin is alive, infinite and irreducible. I had aspired to create a portrait of the city and its people, but in the wake of that aspiration I began to decipher a self-portrait.

I flew back to Seattle with a sense of relief, intent on staying as true to the real Berlin as I could, but accepting that I would never get it right.

In the end, including those first two years of research, the project took me 24 years to complete. I missed my original deadline by 10 years, drawing the last page a few days before my 50th birthday. The book ends in 1933, with the ascension of Adolf Hitler to the chancellorship, and I wrote and drew that portion in Vermont, while the 2016 presidential election was unfolding. The resonance between the story I was telling and the present-day ascension of authoritarianism was powerful and stupefying. At first I thought it a strange and unfortunate coincidence. Now I’m not so sure.

I chose the subject of Weimar Berlin in 1994, on impulse. With some distance now from the finished book, and through speaking about it in public, I’ve managed to peel back the layers underlying that impulse. The first thing I came to understand is that what felt like a random decision at the time actually came out of a powerful unconscious need to educate myself about the circumstances leading up to World War II and the Holocaust (an unfortunate void in my poor public school history education). Beneath that, I was trying to come to terms with the (largely) male capacity for dehumanization, oppression and mass slaughter. Beneath that, I was trying to process my own country’s history of atrocities, and to what degree I personally am implicated in that history. It turns out that only by looking far away in time and space could I begin to look at myself.

Over all of the years I worked on this book, most of my various studio spaces were subterranean – basement rooms, often windowless. I would make my morning coffee and walk downstairs to write or draw about Berlin between the years 1928 and 1933. I was writing about the Bloody May while the WTO protests of 1999 were happening outside my front door in Seattle; I was writing about the Crash of 1929 during the global financial crisis of 2008; I was writing about the rise of fascism in the late 1920s during the rise of global fascism in our current moment. When I walked down those stairs I was traveling back in time and descending into my own unconscious, but I was also listening.

I don’t have any special talent in this regard. I believe anyone able and willing to take the time out of their life to listen can sense the greater trajectory of human civilization. I can draw pictures fairly well, and comics is a narrative art form currently enjoying some popularity, so I’m privileged and fortunate enough to be able to make half a living reporting back from my underground listening post.

The real question now, for me, is what to do with these messages.