Germany’s greatest revolution, one hundred years ago

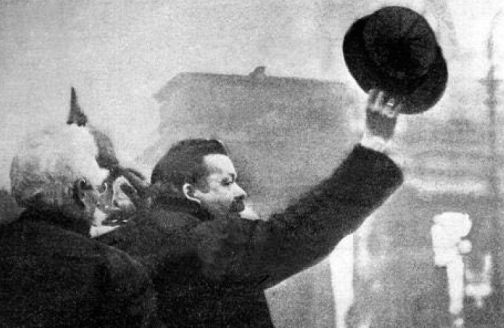

True Republican: Future President Friedrich Ebert speaks at the Brandenburg Gate on Nov. 9, 1918. | photo credit: DPA

True Republican: Future President Friedrich Ebert speaks at the Brandenburg Gate on Nov. 9, 1918. | photo credit: DPA On Nov. 10, 1918, the prominent editor-in-chief of the liberal daily Berliner Tageblatt, Theodor Wolff, published a remarkable commentary on the events that had unfolded in Germany over the previous days: “Like a sudden windstorm, the greatest of all revolutions has toppled the imperial regime together with all it comprised, from top to bottom. One can call it the greatest of all revolutions since never before was such a solidly built and walled Bastille taken at one go. Yesterday morning, at least in Berlin, everything was still there. Yesterday afternoon, all of it had vanished.”

Wolff’s enthusiastic appraisal of the November Revolution may appear surprising, considering that in standard history books, it is generally portrayed as an “incomplete” revolution that failed to create a democracy strong enough to withstand the onslaught of Nazism in the early 1930s. Yet such a verdict only makes sense in retrospect, from the perspective of 1933.

It could be argued that the achievements of the November Revolution – the only successful revolution in a highly industrialized country before 1989 – were quite remarkable indeed: within days, Germany peacefully transformed itself from a constitutional monarchy with limited political participation rights to what was probably the most progressive republic of the period. Germany became a democracy that, despite massive domestic and foreign policy challenges – most of them the consequences of a lost war – lasted for 14 years, thus surviving longer than nearly all of the other European democracies founded in 1918.

It should also be acknowledged that November 1918 not only marked a political revolution, but also a major social revolution that afforded full citizenship rights to women, who had previously been excluded from the most basic right of citizenship: the vote. Germany was the first highly industrialized country in the world to introduce universal suffrage for women and women actually constituted a significant majority of the overall electorate. Although the political history of the Weimar Republic has often been written from a very male perspective, women played a prominent role in the revolutionary events that led to the creation of a democracy and then exercised their democratic rights: in the January 1919 elections for the National Assembly, female voters exceeded male voters by 2.8 million.

The year 1918 also brought the Germans additional freedoms that no one would have thought possible before 1914. Alongside the political reforms that guaranteed equal participation rights for all adult Germans, there were now greater sexual freedoms, both for women and for homosexuals of both genders. Gay rights’ activists immediately responded to the November revolution with considerable enthusiasm, viewing it as the dawn of a new era of sexual liberation that heralded the decriminalization of homosexuality. “The great revolution of the past weeks must be welcomed with joy from our point of view,” wrote Magnus Hirschfeld, leader of the world’s first LGBT rights’ organization, in November 1918.

Not everyone, of course, shared Wolff’s or Hirschfeld’s enthusiasm. Contemporary reactions to the events of November 1918 in Germany were, as one would expect, extremely varied. The conservative Heidelberg-based medievalist Karl Hampe described the revolution from the perspective of a middle-class conservative when he wrote that to him, Nov. 9, 1918, marked the “most wretched day of my life!” Others went even further in their despair. Distraught at the collapse of Imperial Germany and faced with an uncertain financial future, Albert Ballin, the Jewish shipping magnate and personal friend of Wilhelm II, committed suicide that very day. Ballin, the head of Hapag – once the world’s largest shipping company – was simply unable to cope with the perceived bleakness of the present and future.

Irrespective of whether one considered the events of November 1918 as a threat or an opportunity, there was one thing on which all contemporary observers agreed: that the events of November 1918 constituted a proper revolution, or, in the words of the monarchist newspaper Kreuzzeitung, a “cataclysm such as history has never seen.” From the extreme right to the communist left, no one in autumn 1918 seriously questioned that a major revolution had occurred in Germany – a judgment that differs significantly from that of subsequent generations of political commentators and historians. The latter two groups have been far more hostile in their assessment of the events of November 1918 than contemporaries, labeling it a “failed,” “incomplete” or even “betrayed” revolution – a judgment primarily informed by their retrospective knowledge about how Weimar ended.

Because the new political leaders in 1918 left pre-existing economic and social relations, state bureaucracies and the judiciary relatively untouched, and because of Weimar’s eventual demise in 1933, the November Revolution is frequently seen as an “incomplete“ revolution of secondary importance. Some have even doubted whether the events of November 1918 qualify as a revolution at all.

How did this remarkable re-definition of the events that occurred in Germany in late 1918 come to be? The changing perception of the revolution began in 1919 when the overwhelming initial support for the democratic revolution of 1918 was weakened for a number of reasons, not least because many Germans had harbored unrealistic expectations about what a revolution could achieve and how the democratization would affect the peace treaty drawn up by the victorious Allies from January 1919 onwards.

While those on the far left had been longing for a revolution, it was not this revolution to which they had aspired. Like their leaders in 1918, Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg, they perceived the military collapse of Imperial Germany in November 1918 as a historically unique opportunity to create a socialist state run by the workers’ and soldiers’ councils. Friedrich Ebert’s unshakable determination to hold a general election for a constituent National Assembly to answer the question of Germany’s future form of government was portrayed by the far-left as a fundamental “betrayal,” for it prevented the realization of their own, more radical ambitions for the re-organization of German society and its political systems.

The “betrayal” of 1918–19 escalated tensions between different factions of the German labor movement, as the far left felt that the majority Social Democrats under Ebert had prevented a “real” revolution at a time when it was allegedly feasible – an accusation that can still be heard today. As late as 2008, the then chairman of the far-left Die Linke openly declared that Ebert’s “betrayal” of the workers’ movement in 1918 had “set the course for the disastrous history of the Weimar Republic.”

The Social Democrat leadership under Ebert also had high expectations in the autumn of 1918: if demobilization and democratization could be achieved without resistance from the old elites, Germany would be offered moderate peace conditions that would allow the country to emerge from the war as a strong democracy and an equal partner in the post-war international order.

This hope was shared by many bourgeois liberals, even if they had not initially been supportive of a political revolution. Many of them were positively surprised by the lack of radicalism and the relative absence of violence in November 1918, noting with relief that neither chaos nor civil war spread immediately after the takeover that day.

For the prominent theologian and philosopher Ernst Troeltsch, whose “Spectator Letters” are among the most widely known contemporary documents of the period, the greatest uncertainties had already disappeared by Nov. 10: “Not a man died for Kaiser and Reich! All civil servants are now working for the new government! All duties of the state will be carried out and there has been no run on the banks!” Thomas Mann had similar thoughts when, on Nov. 10, he reflected on the events of the previous day: “The German Revolution is a very German one, even if it is a proper revolution. No French savagery, no Russian Communist excesses,” he noted with relief.

What changed this perception, and contemporaries’ retrospective assessment of the November Revolution more generally, was the revolution’s radicalization and its violent escalation in early 1919. The Spartacist Uprising of January 1919, the Munich Soviet Republic later that spring and the brutal backlash by right-wing Freikorps volunteers seemed to many contemporaries to be an unwelcome echo of the Russian Civil War. Similarly disappointing for many was that the expectations for a negotiated peace clashed brutally with the actual conditions of the Versailles Peace Treaty. The nationalist right in particular was quick to portray this as proof of the Republic’s inability to negotiate a better future for Germany. In the collective memory, the revolution, military defeat and its principal consequence – the Versailles Peace Treaty – gradually merged into one narrative in which the revolution, an act of betrayal of the fighting men on the front, had caused an unnecessary military defeat.

No one exploited this soon-to-be widely shared narrative of betrayal and failure more persistently and successfully than Adolf Hitler. Exactly five years after the proclamation of the German Republic, on Nov. 9, 1923, he first attempted his “national revolution” in Munich. He had consciously chosen this date for his futile bid to revise the result of “November 1918” and to instigate a “re-birth” of the German people. During his subsequent imprisonment, Hitler penned Mein Kampf, in which Nov. 9, 1918, featured prominently as his alleged moment of political awakening. For the Nazis, the day became a date of annual mobilization, a date on which Hitler’s followers were called upon to “honor the fallen” of the failed putsch by working towards the replacement of the hated system established in 1918 with a mythical Third Reich.

The fact that a mere 15 years separated the revolution of 1918 from the advent of the Third Reich in 1933 reinforced the tempting (but misleading) interpretation of the “doomed“ Weimar Republic post-1945. Weimar was portrayed as a negative template against which the Federal Republic compared favorably as a much more stable, more Westernized and more economically successful democracy. However, such a perspective ignores that – at least until the beginning of the Great Depression in 1929 – the Weimar Republic was relatively stable. Extremists on the far left and right had been marginalized, Germany’s international isolation was overcome and the SPD had won a landslide victory in 1928. From the perspective of 1928, the Republic’s survival would have seemed a great deal more likely than its failure.

Our perspective on 1918 has also for too long been dominated by a national tunnel vision that largely views events in Germany in isolation from what was going on elsewhere in Europe. The year 1918 was part of a much larger European moment of political change. Between 1917 and 1920 alone, Europe experienced some 27 violent transfers of political power. Russia in particular experienced two revolutions within less than 12 months, eventually resulting in a civil war that cost the lives of well over three million people. It is also worth noting that of all the parliamentary democracies created in East-Central Europe after 1918 (with the exceptions of Finland and Czechoslovakia), the Weimar Republic was one of the last democratic states founded in 1918 to give way to an autocratic regime.

A broader perspective is also important when it comes to determining the place the German Revolution should hold in modern European history. Both the great European revolution of the West (the French Revolution of 1789) and the great European revolution of the East (the Russian Revolution of 1917) quickly led to civil wars and dictatorships without anyone denying their historical significance. Even compared to other European revolutions – those in Finland and Hungary in 1918 and 1919 – the revolutionary events in Germany were not only relatively bloodless but also remarkably successful when measured against their objectives: the restoration of peace and the replacement of the monarchy with a democratic regime. The Ebert government succeeded in channeling revolutionary energies, maintaining public order in the face of a historically unprecedented defeat and peacefully demobilizing several million soldiers.

In view of the enormous challenges that the emerging Weimar Republic faced, Theodor Wolff’s comment that the German Revolution of 1918 was the “greatest” of all revolutions may appear daringly optimistic, perhaps even naïve. Nevertheless, one hundred years after the Revolution, it might be time to do more justice to an event that led to the creation of the most progressive republic of its time and that was – at least initially – accompanied by great hopes and expectations for a yet unknown future.

Robert Gerwarth

is Professor of Modern History at University College Dublin and director of the Centre for War Studies. His book Die größte aller Revolutionen: November 1918 und der Aufbruch in eine neue Zeit (The greatest of all revolutions: November 1918 and the beginning of a new era) was published in September 2018.