Greater Berlin: In 1920 Adolf Wermuth created the modern metropolis

Good luck: Bruno Taut’s Horseshoe Estate, 1930

Good luck: Bruno Taut’s Horseshoe Estate, 1930Credits: bpk-Bildagentur (6) VG-Bildkunst

Many streets in Germany bear the names of individuals who served the common good in one way or the other. In Berlin, this honor is often bestowed upon people whose names are unfamiliar to the broader public and whose merit and deeds are equally unknown. Yet there are also plenty of individuals who have had a huge impact on the city but go entirely neglected when it comes to street names. One such individual is Adolf Wermuth, who has only one street in Berlin named after him. Wermuthweg is a small concrete-slab lane sandwiched between high-rise apartment buildings in Neukölln, far removed from Berlin’s city hall known as the Rotes Rathaus, where this man accomplished a most impressive feat.

Adolf Wermuth was responsible for paving the way to Berlin becoming a modern metropolis. How did he do it? Roughly one hundred years ago, as Berlin’s mayor, he enacted legislation that merged dozens of surrounding districts, cities and Brandenburg municipalities together with the core city districts of Berlin. On Oct. 1, 1920, although he was not affiliated with any specific party himself, Wermuth was able to push through the legislation by drawing on the support of left-wing parties in the parliament, while the centrist parties and the National People’s Party voted against it.

There was plenty of resistance to the plan from other forces as well. Brandenburg did not take kindly to the loss of land and taxpayers, and the rich municipality of Charlottenburg expressed very little interest in sharing its wealth with the poor Berliners at the city’s historical core. But Wermuth was able to win them all over. The result was an overnight increase of 1.9 million “new” people added to the already 1.9 million inhabitants of Berlin. The city’s surface area increased from 67 to roughly 878 square kilometers. Only Los Angeles was greater in area at the time, and only New York and London had larger populations. The city’s original six districts now became 20, and Berlin would soon be the largest industrial city in Europe, with its own airports and Autobahn. Having quickly become a modern and liberal cultural metropolis, the city was now called Greater Berlin.

Once the legislation passed, policymakers could start regulating what had, until then, been a state of municipal anarchy in which “one community digs up the water of the other,” as described by Alexander Dominicus, the mayor of Schöneberg. In Greater Berlin, it became possible to plan and build joint electrical grids, water systems and transport networks while also addressing social problems such as housing shortages and food supplies.

Thirteen years later, however, another Adolf came to power with a desire to make the proud city even bigger: Adolf Hitler harbored dreams of creating his “Germania,” the capital of the world. Instead, however, his vision resulted in Berlin being reduced to rubble and ashes. Most of what had been built since 1920 was destroyed, and the city’s inhabitants lived in precarious conditions, facing deprivation and even starvation. Hitler and his cronies disappeared, and the streets that had been renamed for them were renamed once more. Hundreds of thousands of people had also disappeared, and factories and banks turned their back on the divided city that was now cut off from the rest of the world.

Today, 30 years after Germany’s reunification, Berlin has almost as many inhabitants as it did 100 years ago. Adolf Wermuth has been laid to rest in peace in a cemetery in a northern Berlin neighborhood and even has an honorary grave maintained by the city of Berlin. However, officials still haven’t found an appropriate street to name after him. In the district of Mitte, there are stipulations that an equitable number of streets be named after women and that no two streets should have the same name. But sometimes these rules are ignored – visitors to the city should know that when they hop in a taxi for Goethestraße in Weißensee, they just may end up in Charlottenburg.

The good Adolf: Adolf Wermuth, mayor of Berlin from 1912–1925

Credits: picture alliance/ullstein bild (Wermuth)

Bright lights, big city: Potsdamer Platz in 1930

Yep, that’s a department store: Karstadt in Neukölln, 1929

Legendary: Erich Mendelsohn’s Mossehaus in 1923

Big screen: Universum movie theater, 1928

© bpk / Kunstbibliothek, SMB / Arthur Köster

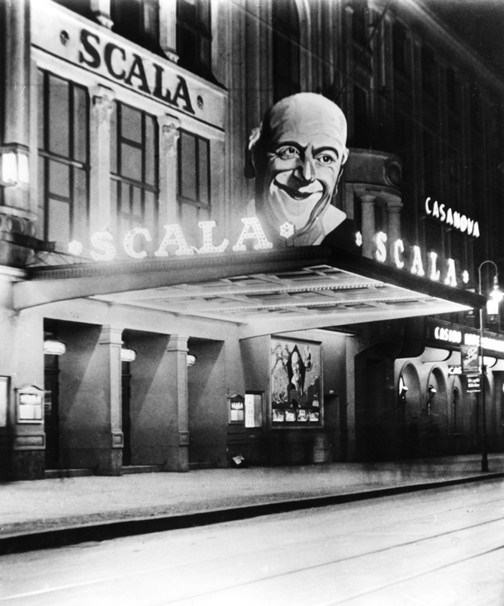

Big stage: Scala Theater in 1929

Peter H. Koepf

is editor in chief of The German Times. Together with Franziska Schreiber he wrote the best-selling book Inside AfD. A Report by One Who Left, which was published in German in August.