More than just architecture: Frankfurt has its historic Old Town back

A number of architects had already started issuing prophecies of doom. Indeed, back when planning was underway to reshape the center of Frankfurt, word on the street was that it was destined to become a “gebaute Lüge,” that is, the architectural embodiment of a blatant lie. Some even used the word “Disneyland,” in Europe a synonym for a flashy, superficial world of make-believe. Critics of the plans went so far as to play a card that is often highly effective when it comes to muzzling opponents in any debate in Germany: the Nazis, they noted, had also been fans of the half-timbered building style known as Fachwerk.

That was in 2006, when the debate over developing the area between the cathedral and the Römer – as Frankfurt’s city hall is called – had reached a boiling point. The positions on both sides were irreconcilable: one party was advocating a reconstruction of the pre-war configuration, while the other promoted a full embrace of modern architecture. The former rhapsodized about the rebuilding of historically significant buildings, while the latter urged that architecture should reflect the style of its time – returning to the building forms of past eras would be escapist.

The area over which the traditionalists and the modernists were so bitterly fighting is tiny. Although it measures no more than 7,000 square meters, it is of eminent historical and urban significance: it constitutes the core of old Frankfurt. The Romans chose to settle there due to the site’s slightly raised elevation, which offered flood protection from the nearby River Main. Centuries later in 794, Charlemagne convened a synod here; the Carolingians built a palace in 820; and from 1562 onward, the Holy Roman kings and emperors were selected and crowned here in the cathedral, before setting out on the coronation path to the feast in the Römer. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe witnessed one such coronation as a boy and raved about decades later in his autobiography.

In short, there were few locations in Germany more historically charged than this one, even if no one in post-war Frankfurt could appreciate it. After the entirety of the Old Town fell victim to Allied bombs, Frankfurt – more recklessly than most other German cities – simply cleared away the rubble and proceeded on a rather radical track toward modernism. At the beginning of the 1970s, the area between the cathedral and the Römer saw the construction of a massive concrete complex, built to house the city government’s technical offices. The 10-story Brutalist building was a monument to historical amnesia.

When the monstrosity became derelict 30 years later, there was suddenly a chance to start all over again, but the local administration was surprisingly unprepared to seize the opportunity. At the beginning of 2005, an urban development ideas competition was launched with rather vague guidelines. The invited architects proceeded to deliver rather unimaginative designs with façades clad in the prevailing styles of the day. Had they been realized, the cathedral- Römer area would now be populated with faceless buildings whose demolition would be under discussion within just a few decades.

But then a small, conservative faction of the city council wrote a proposal to alter the foreseeable course of action: the “Citizens for Frankfurt” called for re-establishing the layout of the historic Old Town and reconstructing the buildings of particular significance from an art history perspective. In light of the dismal designs produced by the architecture competition, the idea quickly gained resonance among political outsiders. For a few months, the municipal public could talk about nothing else; informational events and panel discussions were consistently well attended. The voting results were unambiguous, as polling had also indicated: an overwhelming majority of Frankfurters expressed their support for the re-instatement of the pre-war architecture and edifice in the area between the cathedral and the Römer.

For Frankfurt, this whole debate was highly unusual. Seldom in recent decades has the city discussed architecture and urban development so intensely. The citizens had become accustomed to the ever-changing appearance of their city; no other place in Germany has consistently experienced such short iterations of “new construction – demolition – new construction.” And no place has a higher tolerance for benchmark-busting buildings. In an economic sense, Frankfurt has profited enormously from this development; it never managed to forge a satisfactory look for itself, even if its skyline of skyscrapers – no other city in Germany can rightfully use the phrase – has since defined its image, and with much popular approval.

The causes for this shift in opinion are ripe for speculation. In a certain sense, the theme had been floated some time ago. The rebuilding of the Dresden Frauenkirche was completed in 2005, while many other German cities were also discussing reconstruction projects, not least Berlin, where certain groups were struggling to rebuild the Prussian palace in the center of town. In cases where the erasure targeted former East German initiatives, the projects could be justified as a correction of the GDR’s politics of memory. In terms of projects in former West German states, planners were wary that Germany was mired in an economic crisis – the phrase “sick man of Europe” was not uncommon at the time. The popularity of historical reconstructions was also a manifestation of anxieties about the future, especially in the bourgeois middle class that dominated the debate on the redevelopment of the Old Town. Frankfurters openly yearned for a city image that people would unequivocally associate with better times.

The establishment parties in Frankfurt’s city hall initially sought to diminish the uncharacteristically vehement citizen participation, but it gradually found its way into the debate as its representatives delved deep into all relevant materials. In a protracted yet fruitful process, the project began to take shape – 15 buildings were to be reconstructed and 20 plots would give rise to new constructions that would be forced to adhere to rather rigid design stipulations. As such, the ensemble would emerge. The relevant statute called for steep pitched roofs that were covered in slate, had natural stone skirting and featured only gabled windows. And then there was the so-called Stadthaus, or town house, whose lower story comprised the remaining walls of a Roman station and the Carolingian palace.

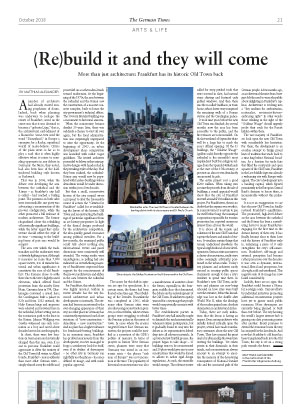

It took nine years before the new Old Town was finished; for several months now the area has been accessible to the public, and the first tenants are now installed. On the last weekend of September there will be a large fair to mark the area’s official opening. Of the 35 buildings, the “Goldene Waage” (golden scale) directly opposite the cathedral is the ensemble’s most resplendent: built by a religious refugee from the Spanish Netherlands at the start of the 17th century, it presents an almost overabundantly ornamented façade.

The entire project cost a good €200 million. When taking into account the proceeds from the sale of buildings, a sound appraisal would show that the city of Frankfurt invested around €130 million in this project. For Frankfurters, there is no doubt that the expense was worth it. In concrete terms it is certain to pay for itself before long: the municipal corporation responsible for tourism promotion has reported enormous interest from all over the world.

It is above all the variety and coherence of the new Old Town that capture the hearts and minds of visitors. It visualizes certain things that remain undisclosed elsewhere: the typical neighborhood of new development in German cities amounts to a cluster of monotonous, multi-story cubes seemingly arbitrarily positioned in the urban realm. Today’s city planners and architects rarely succeed in creating public spaces charismatic enough to lure a city’s residents to spend time there. In Frankfurt’s new Old Town, architects and planners are now being schooled on how cities were built over the centuries, before this knowledge was lost in the shuffle after World War II, when the ideology of the modern gained near absolute domination in architectural circles.

Today, there are early indications that the lesson is having an impact. Even among architects who initially looked critically upon the project, several have made conciliatory statements about the new Old Town. They have praised the great deal of craftsmanship that went into erecting the buildings. Yet others persist in their dismissals; in their minds, such reconstructions always amount to an attempt to amortize the memory of the devastating consequences of National Socialist rule and the associated guilt of the German people. A few months ago, an architectural theorist from Stuttgart felt the need to warn the public about delighting in Frankfurt’s replicas. Architecture is evolving into a “key medium for authoritarian, nationalist, revisionist-history-embracing right.” In other words: those relishing in the sight of the “Goldene Waage” should urgently probe their souls for the Fascist hidden within them.

The vast majority of Frankfurters look upon the new Old Town with considerably less hesitation. For them, the development is an overdue attempt to bridge proud lines of tradition that reach back to a time long before National Socialism. As a location for trade fairs that filled the courtyards and open squares of the Old Town, Frankfurt in the Late Middle Ages was already a welcoming city with Europe-wide appeal. The city’s development into a banking capital, which figured prominently in the European Central Bank’s decision to locate there, is inconceivable without this prehistory.

It is not an exaggeration to say that the new Old Town has finally restored Frankfurt’s equilibrium. The protracted, high-level debate on the area between the cathedral and the Römer has been a contributing factor to many Frankfurters engaging for the first time in the distant history of their city. It has finally become clear to them how rich the history of Frankfurt truly is; reclaiming a piece of it only strengthens the city’s self-awareness. Frankfurt’s self-image and external perception had become rather precarious over the decades: it was seen as dynamic, international, liberal and prosperous, but also ugly, cold and untethered. This negative side of its image has now faded considerably.

Luckily, there are no signs that Frankfurt could become a Mecca for nostalgic souls. Current efforts by individual initiatives promoting additional reconstruction projects have yet to garner much public resonance. More skyscrapers are currently being planned or built than ever before. The city housing the world’s largest internet hub is gaining one data processing center after another. Brexit promises to extend the economic boom the city has enjoyed for the last decade. And now that Frankfurt’s old heart has been transplanted back into the Old Town, the city is set on a strong path towards the future.

Matthias Alexander

is the metro chief of the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung.