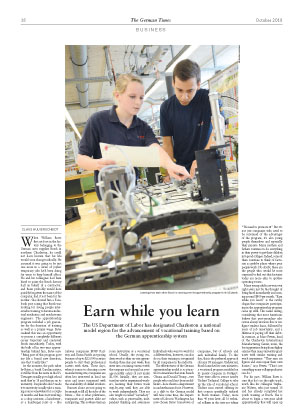

The US Department of Labor has designated Charleston a national model region for the advancement of vocational training based on the German apprenticeship system

When William Bates first set foot in the factory belonging to the German auto supplier Bosch in northern Charleston, he could not have known that his life would soon change radically. He assumed it was going to be just one more in a series of joyless temporary jobs he’d been doing for years to keep himself afloat. He and his colleagues had been hired to paint the Bosch factory hall on behalf of a contractor, and Bates probably would have quickly forgotten the name of the company, had it not been for his mother. She showed him a Facebook post saying that Bosch was looking for young people interested in training to become industrial mechanics and mechatronic engineers. The apprenticeship program included a job guarantee for the duration of training as well as a proper wage. Bates realized this was an opportunity to pursue a completely different career trajectory and contacted Bosch immediately. Today, with the bulk of his two-year apprenticeship behind him, Bates says: “Being part of this program gave my life a brand new direction, one that I really like.”

At the moment, the path taken by Bates, a South Carolina native, is still far from the norm in the US. Teenagers usually go to high school until they’re 18 and then go on to university. People who don’t make it to university usually take a training course somewhere for a couple of months and then start working: as a shop assistant, a hairdresser, at a hamburger joint or – like Bates – in construction. The idea of completing an apprenticeship based on the German model – which includes on-the-job training, classroom instruction and payment of a living wage – continues to be the exception.

However, over the past several years, it has become increasingly clear how ill-equipped the traditional US education system is to deal with an ever more demanding job market. The unemployment rate is at barely 4 percent, and the lack of skilled workers is palpable throughout the country. In Iowa, for example, companies are lining up at technical colleges to snatch up the best young graduates. The railway companies BNSF Railway and Union Pacific are paying bonuses of up to $25,000 to entice people to start their professional careers with them. These days, when it comes to choosing a new manufacturing site, companies are often less interested in local tax rates and more concerned with the availability of skilled workers.

Bonuses alone are not going to be enough to fill all the jobs of the future – this is what politicians, companies and parents alike are anticipating. This is where German companies come in; they’re helping to rethink the system. When setting up their subsidiaries in the US, these companies are bringing not only German engineering, thoroughness and traditions to the table; they also have the so-called “dual education system” in tow. This apprenticeship model is considered a masterstroke in terms of next-generation workforce training in Germany. Indeed, it is most likely one of the key factors determining the success of so many German industrial companies throughout the world.

The dual education system has two components: on-site training at the company itself and classroom instruction at a vocational school. Usually, the young students work at their on-site apprenticeship three days per week; they enter into a training contract with the company and are paid an average monthly salary of just under $1,000. Initially, they are mentored on-site by experienced workers, learning their future trade step-by-step until they are able to work independently. They are also taught so-called “secondary” values, such as punctuality, independent thinking and awareness of rules regarding such things as workplace security and accident prevention.

The apprentices spend the remaining two days of the week at a local vocational school together with trainees from other companies. In addition to gaining special knowledge about each individual profession, the students usually take weekly courses designed to deepen their overall education, including subjects like politics, communication and PE. The entire program usually lasts three years and ends with a theoretical and practical examination. Many graduates are then taken on as employees by their companies. Individuals who want to work for a different firm, however, can also do so; their training is recognized by all companies in the industry.

The effectiveness of the German apprenticeship model is so attractive to Americans that even Barack Obama and Donald Trump – two people who could not be more different – have shown a deep interest in and enthusiasm for it. However, as a shift to the German model will take some time, the Department of Labor in Washington has now chosen Bates’ hometown of Charleston – a town that just so happens to be the US base for German companies such as Bosch, Daimler, BMW, IFA and Evonik – as a national model region for the advancement of vocational training.

When Bosch set up shop in South Carolina almost 50 years ago, the idea of generating skilled workers via German-style youth apprenticeship programs was unthinkable. Back then, most US companies would have seen paid on-site workforce training as incongruous and outlandish, especially because the responsibility for training young workers for skilled jobs was not that of the companies, but of schools and each individual family. To this day, this is the preferred approach of many US managers. Undeterred, Bosch launched its own initiative, a vocational program modeled on its parent company in Stuttgart. They were able to attract nearby Trident Technical College to take up the role of vocational school. Trident soon started offering its first courses specifically tailored to Bosch trainees. Today, more than 40 years later, all 16 technical colleges in the state are taking part in the Apprenticeship Carolina program. More than 28,000 employees have completed apprenticeships since then, whereby most of the roughly 1,000 participating companies draw a clear distinction between first-time apprenticeship training and further education for existing employees. The majority of the “apprentices” are in fact employees who have been working at the company for a longer period of time.

Among the most enthusiastic supporters of the apprenticeship offensive is Bryan Derreberry, president of the Charleston Chamber of Commerce. “Talent is the oil of the 21st century,” he says. “We need to promote it!” But it’s not just companies who need to be convinced of the advantages of the program; it’s also young people themselves and especially their parents. Many mothers and fathers continue to do everything in their power to get their children into good colleges. Indeed, some of them continue to think of factories as grubby places where poor people work. No doubt, these are the people who would be most surprised to find out that factories today are more akin to spotless operating rooms.

Many young adults are won over right away just by the thought of being hired immediately and earning around $800 per month. “Earn while you learn” is the catchy slogan that companies participating in the apprenticeship program came up with. This seems daring, considering that most Americans believe that post-secondary education always involves five or six-figure student loans, followed by years of job uncertainty, and a lifetime of paying off their debts. In contrast, as Marc Fetten, head of the Charleston International Manufacturing Center, notes, the best apprentices bring home higher salaries than many university graduates with similar training and work experience: “They earn six figures and even repair their own homes,” says Fetten. “That’s not something many college graduates can do.”

For his part, William Bates is sure that he’s on the right track, much like his colleague Stephanie Walters, who just turned 18 and has already completed her youth training at Bosch. She is about to begin a two-year adult apprenticeship that will open up even more career opportunities. She plans to follow that up with an engineering degree, which will take another two years and be financed by Bosch. Throughout those four years, Walters will continue to work at the company and bring home a salary. “I plan to be finished when I’m 22 and have all the opportunities I need,” she says. “At that point, most of my friends entering college now will be just starting to think about how to pay off their student debt.”

Claus Hulverscheidt

is a US correspondent for the Süddeutsche Zeitung.