Why a young Berliner at Oxford founded a science publication for refugees

Sandra Maischberger’s TV talk show in the fall of 2015 was drawing to a close when she gave the last word to a guest from the audience. In nearly accent-free German, Hakim spoke about his studies in Syria, his trek across the Mediterranean and his new job as a geriatric nurse in a small town in Lower Saxony. Before applause broke out in the studio, a caption showed viewers at home who exactly this exemplary young Syrian was: “Hakim, refugee.”

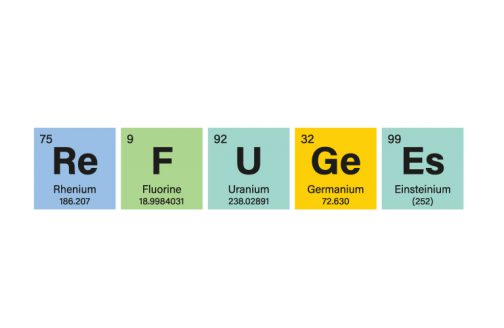

It was a revelatory moment in a debate on the dangerous denigration of those refugees who had fled to Europe in the summer of 2015. Hakim can vouch that the word “refugee” had become a new label almost overnight. The German word for “refugee,” Flüchtling, has the diminutive suffix ling, implying that a person must somehow be pitiable as well as from a distant, unknown culture. Reports frequently painted the same image in different shades of negativity.

It was also a rather liberating moment, as this was one of the first opportunities for a refugee to represent himself in the “refugee debate.” The daily reportages, comments and interviews on the new “task of the century” (Angela Merkel on Jan. 14, 2016) had all been delivered by politicians – it remains the exception that a person who had himself fled to Germany was given a voice.

There was widespread disregard for the fact that most refugees brought much more to Europe than a bundle of clothes. Some brought their knowledge: in their native countries they had been professors, students and researchers. To treat them only with compassion, regrettably, often meant leaving their knowledge and expertise untouched and thus limiting any intellectual exchange or discourse.

My fellow students at Oxford University and I were preoccupied with the subject in the fall of 2015. To facilitate a new discourse in this situation, my roommate Mark Barclay and I founded the Journal of Interrupted Studies. It was to become an academic journal that would give refugee scientists the opportunity to publish their finished and unfinished articles in all disciplines.

At 19 years of age, none of us had the capacity to assess the academic relevance or integrity of articles written by professors and researchers. So we set up a multi-level peer-review process, as is common with scientific publications: subject matter experts receive and rate the essays without being told the name and history of the author. Texts were to be selected based on their quality, not on their author’s biography.

We were hoping to change the perception of refugees and counteract the understandable fears many people have; they may be less fearful if they realize that refugees are concerned with the same issues as they are. Through contributions on television and in print media, we were able to cast a better light on refugees, one that would reach far beyond our academic audiences. At the same time, we wanted to send a message to the academic and political world: the knowledge and diversity of discourse are jeopardized when refugee academics are not given a perspective. Our biggest hope, however, was that our publication would enable and inspire our authors to pursue their academic careers.

Countless submissions started flowing in. Many of them focused in some way on migration: an article by a lawyer from Bangladesh argued that people displaced by natural disasters should be integrated into the international legal system. A Syrian student visited schools during the civil war in order to ascertain whether, in the future, robots could replace missing teachers. The linguist Husam Aldeen al-Barazy from Damascus described the importance of intonation when learning new languages. He had fled Syria, and now lives in the tranquil German town of Düppenweiler in Saarland.

Gaining the authors trust involved a great deal of responsibility. We set about building a small editorial office and recruiting the first academics for peer reviews. The vast majority was surprisingly open to our project, enlisted more of their colleagues and added us to their mailing lists. But we were missing one crucial component: €1,500 to cover printing expenses. We started getting our first donations and by May 2016 we were able to publish the first issue.

As expected, there were mixed feelings: while BBC, NPR and the German weekly Der Spiegel gave us a warm welcome, we received quite a few hateful remarks on social media: “The only knowledge these people bring with them is rape,” was one. The totality of reactions, however, showed us that the project had found an audience.

While the first issue was self-published, we were able to acquire funding from the German Academic Scholarship Foundation and work with the Dutch publishing house Brill to publish our second edition. Our new budget finally allowed us to pay the authors an honorarium, albeit a very small one.

In 2018, not only did German migration policy change, the origin of our authors did as well. Turkey had replaced Syria and Iraq, which presented the editors with new challenges. For example, the migration stories were often comparable to those of many Syrian academics; in addition to civil wars, environmental disasters and political persecution were now prominent factors; fleeing across the Mediterranean has in many cases been replaced by resettling in a more peaceful region of migrants’ home countries.

Therefore, in addition to translators, we also had to establish some new guidelines: Who should decide whether an author is actually considered a “refugee”? We chose to leave that classification to the authors themselves, to those who were expelled or had to flee.

We are now working on the third edition, and one new factor is the institutionalization of the journal. We are working to create legal and editorial structures that will ensure the survival of the project regardless of whether we stay on as publishers.

Published in “The Berlin Times – A special edition of The German Times marking October 3rd, the Day of German Unity.”

Paul Ostwald

The 21-year-old Oxford student is the co-founder of the Journal of Interrupted Studies.